Pen shells are common but far from boring

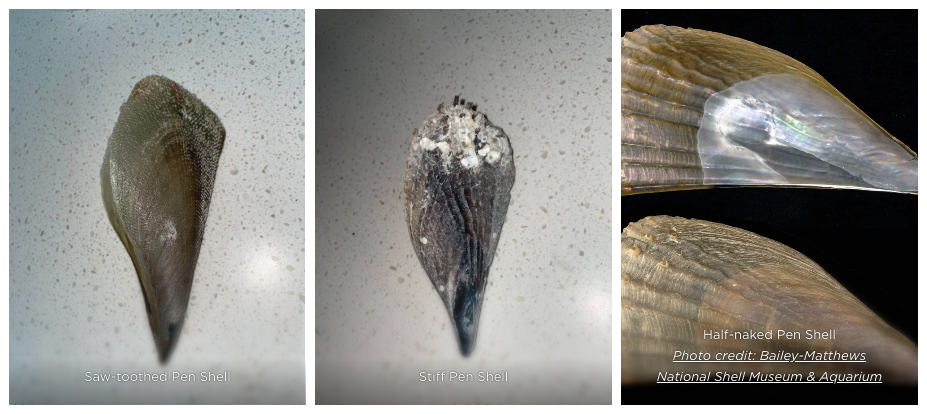

When you visit the beaches of Sanibel and Captiva, you will inevitably be greeted by an abundance of pen shells littered throughout the wrack line. Two species of these beautiful, fan-shaped bivalves are frequently seen: the stiff pen shell (Atrina rigida) and saw-tooth pen shell (Atrina serrata). But there exists a third that is rare to find in Southwest Florida: the half-naked pen shell (Atrina seminuda).

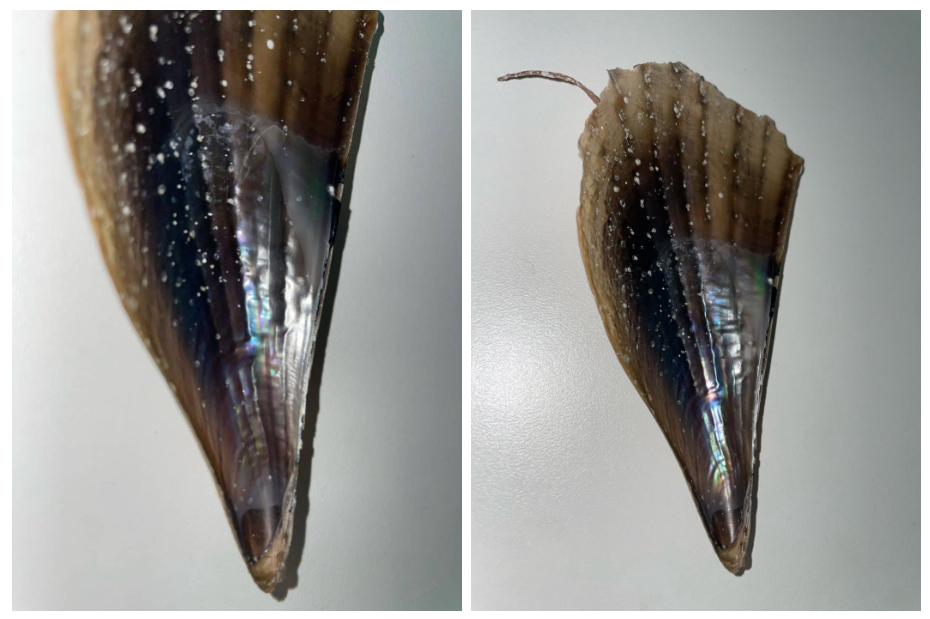

Pen shells are easily distinguished by their size, shape and iridescent nacreous layer. The stiff pen shell and saw-tooth pen shells are relatively easy to tell apart. Stiff pen shells are tough, dark brown and rigid, while saw-tooth pen shells are lighter in color and have much smaller spines that don’t stick out. Where it gets tricky is distinguishing between the very common stiff pen shell and rare half-naked pen shell. The only way to really tell them apart is by looking at the muscular scar inside the shell. The large muscular scar is well within the border of the nacreous layer for the half-naked shell, but crosses over the border of the nacreous layer for the stiff pen shell.

Pen shells are some of the largest bivalves found around the world, growing up to a size of about 10 inches. They are efficient filter feeders that bury themselves almost entirely in the sand, leaving only their razor-sharp tops exposed. Sadly, they get a bad rap because they’re often the culprit behind cut feet at the beach. Despite their sharp edge, they’re still preyed upon by other creatures, like horse conchs and sea stars. The ocean does not let munched-on pen shells go to waste. They provide excellent habitat for encrusting creatures, like barnacles and slipper snails, other snails like to anchor their egg casings to them, and we’ve even spotted little fish like the Florida blenny hiding under them.

We’ve already mentioned the nacreous layer a few times here, and you’re probably wondering — what the heck is that?! Well, if you’ve held a pen shell, you may have noticed the rainbow-colored bottom interior of the shell. This is the nacre layer, also known as mother-of-pearl. It is composed of thousands of thin, flat calcium carbonate crystals that scatter light, creating the characteristic iridescence. The benefit of this in nature is that it creates a strong but lightweight shell.

And just when you thought pen shells couldn’t get any cooler, we haven’t even talked about byssus yet. These silk-like filaments are what anchor them to the sea floor. It’s the same technique that lots of other bivalves, like muscles, use to cement themselves to solid surfaces. Byssus is sometimes called “sea silk” because, in the late 17th century, it was documented as being woven into stockings and mittens. Sea silk is made from a specific type of byssus from the noble pen shell (Pinna nobilis). Fast forward to the present day, and there is only one woman known to continue to weave these precious threads. Chaira Vigo, 62, of Sardinia, while being monitored by the Italian Coast Guard, will dive up to 17 yards in the moonlight to harvest the clams for weaving.

While we can’t get fancy enough to make silk at the Sanibel Sea School, we do find Chaira inspiring, and we use pen shells to make some pretty incredible art with our students. We often collect small, broken pieces from the beach because they make a perfect wave mosaic. Or if you have the whole shell, they make for great fins on a hammerhead shark. We love finding and learning about pen shells in our courses; in fact, we’ve dedicated entire weeks of summer camp to them before. Join us to explore the beach, and maybe we’ll get lucky enough to find the rare half-naked pen shell together.

Austin Wise is a marine science educator with the Sanibel Sea School.